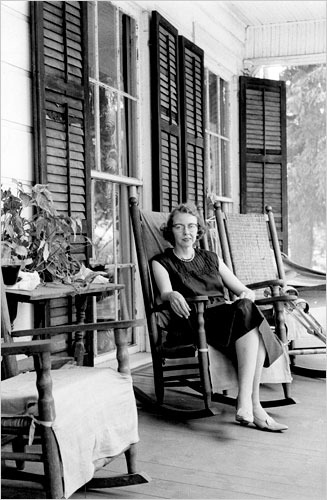

I love Flannery O’Connor, and that makes me a member of a very big club. Most writers I know list her as one of their inspirations.

I liked O’Connor before I even read her work, for one very superficial reason: Our names are similar. If I look at her book from across the room and squint, it almost looks like my name is on a very big book of collected stories.

Then I picked up the book and I learned to love her even more.

There are a lot of things to love. The spiritual nature of her work, her gentle but unflinching treatment of racial inequality in the South, and O’Connor’s dark sense of humor appeal to me. But the thing I love most about O’Connor is the way she creates her characters through dialogue. She believably creates the voices of bratty children, racist old men, gossipy women, pretentious intellectuals and crooks.

That’s no mean feat. Below the break is the craft essay I wrote for my MFA program about the genius of Flannery O’Connor’s dialogue.

Be warned – O’Connor wrote her stories in the early 20th century and dealt with issues of race, so there are some racial slurs in the essay below.

The dialogue and dialects of Flannery O’Connor

Josip Novakovich tells us that it takes more than y’all and reckon to make a Southerner in his craft book, “Fiction Writer’ s Workshop.”

Flannery O’Connor, whose work is synonymous with the Southern Gothic genre, proves this point. Consider the following dialogue, which features not one y’all or reckon:

“Lady,” he said, “for a Chrustian, the Word of God ought to be in every room in the house besides his heart.” – Good Country People

“Take her off and throw her where you thrown the others.” – A Good Man is Hard to Find

“You ain’t been raised that way!” he’d said thundery-like. “You ain’t been raised to live tight with niggers that think they’re just as good as you and you think that I’d go messin’ around with one er that kind!” – The Geranium

The above three passages use different techniques to denote dialect. The first deliberately misspells one word, to give the impression of an accent. The second uses syntax; O’Connor substitutes “thrown” for “threw.” The third uses a combination of the first two techniques, and adds the ethnic slur “niggers.” That word, a pejorative even at the time the story was published in 1953, indicated a certain mentality from a certain part of the country.

Novakovich tells us not to fear the use of dialect, and to use the dialects with which we are familiar. As a Georgia native who lived in both Iowa and Connecticut, O’Connor was intensely aware of the sound of the Southern accent, but she rarely overpowers her readers with the dialect, save in stories like “Wildcat” in which you get dialogue like this:

“Ain’t no reason to be ‘fraid to stay here by yosef, they’d laughed. Ain’t nothin’ gonna git you. We take you up the road to Mattie’s ef you scaird.” (The Complete Stories of Flannery O’Connor, p. 30)

Almost every word in the above passage is changed to denote accent, poverty and race. For me, at least, it is a difficult read. Novakovich appears to agree.

“When using dialect,” he writes, “ don’t alter your spelling radically… Here and there you might alter a word or two, but don’t overdo it, because most readers resent having to slow down.” (p.112)

O’Connor handles dialect in several different ways, in some cases, using it only for one character as in “The Barber.” In that piece, only the barber and his employee seem to speak with an accent.

O’Connor’s genius with dialogue goes beyond regional accents to the portrayal of individual characters and age groups. In “A Good Man is Hard to Find” and “A Temple of the Holy Ghost,” she reproduces, convincingly, the speech of children.

In “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” O’Connor uses dialogue to describe the antics of the grandchildren, the sort of kids most people like to avoid in movie theaters, restaurants and the grocery store checkout line:

“We’ve had an ACCIDENT!” the children screamed in a frenzy of delight. “But nobody’s killed,” June Star said with disappointment… (p.125)

Through dialogue, the reader comes to sympathize with the bratty 12-year-old narrator of “A Temple of the Holy Ghost.” It need not be stated that the reason for the child’s frustration with her 14-year-old cousins is the onset of her own puberty. Her jealousy and rage makes itself felt in her hysterical outbursts of laughter, her screams and her declarations that while her cousins are older, she is smarter.

This story also uses indirect dialogue in the interchange between the cousins and the narrator. Novakovich tells us (p.115) that indirect dialogue is used to emphasize certain points more than others. O’Connor, demonstrates this principle by giving the two 14-year-old cousins, introduced on the first page as not being very bright, very few direct quotes in the course of her story. Almost every other character is quoted directly. Even when the cousins have a lengthy piece of exposition, their words are summarized, while the person the cousins are discussing is directly quoted:

Actually, she had never seen a rabbit have rabbits but she forgot this as they began to tell her what they had seen in the tent.

It had been a freak with a particular name but they couldn’t remember the name. The tent where it was had been divided into two parts by a black curtain, one side for men and one for women. The freak went from one side to the other, talking first to the men and then to the women, but everyone could hear. The stage ran all the way across the front. The girls heard the freak say to the men, “I’m going to show you this and if you laugh, God may strike you the same way.” (p. 245)

In this way, although the cousins are delivering this information, their contribution is trivialized and the freak’s words are made more important than their own.

Throughout all of her stories, O’Connor presents her readers with distinctly-voiced characters who interact with each other vividly. In “The Crop,” we get a strong feeling about the sort of household we are entering when this conversation is presented:

“Willie!” Miss Lucia screamed, entering the dining room with the saltcellars. “For heaven’s sake, hold the catcher under the crumber or you’ll have those crumbs on the rug. I’ve Bisseled it four times in the last week and I am not going to do it again.”

“You have not Bisseled it on account of any crumbs I have spilled,” Miss Willerton said tersely. “I always pick up the crumbs I drop,” and she added. “I drop relatively few.” (p.34)

The dialogue builds the scene, sets the tone and illustrates the character of the two women speaking; a daydreamer and a housekeeper who don’t necessarily enjoy living under the same roof. An author can hardly ask a passage to do more.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!